Baskets of Beauty

In February of 2025, I attended a group exhibit at Tieton’s Boxx Gallery, which included a variety of beautiful baskets created by indigenous and non-indigenous artists from throughout Washington State. The feature image shown above shows the work of Yakama Nation artist Wahpeniat (pronounced “Wah-pen-eye-at”) standing next to a display of her colorful, contemporary-looking baskets, adapted from a traditional, utilitarian, medicinal root and food gathering basket known in the Yakama language as “wa’paas.”

A few weeks after our initial Boxx Gallery meeting, I sat down with Wahpeniat to record an in-depth interview that helped me learn more about her life and the cultural background that provided the original inspiration for her artistic work.

To further understand the details of Yakama history, customs, and spiritual beliefs after speaking with Wahpeniat, I decided to visit the Yakama Nation Museum and Cultural Center in Toppenish, Washington, only a 45-minute drive from my loft in Tieton. In addition to viewing the exhibits themselves, I also wanted to properly introduce myself to the Museum staff as a visual artist and the author of the Art Nun of Central Washington online journal, which would include Wahpeniat’s story as a future post.

I called the museum ahead of time to arrange an in- person meeting with manager Heather Hull, a Yakama Nation member and historical scholar, who graciously shared important information about the museum’s collections. She also outlined the guidelines that visitors needed to understand (quiet contemplative access, and no photos) to ensure that the exhibits would be viewed with respect.

The Yakama Nation Museum and Cultural Center

Although for many years I had thoroughly immersed myself in self-directed historical readings that described the broken promises (and worse) that were carried out by the US government towards native peoples in times past, I was still emotionally unprepared to encounter the palpable despair I began to feel as I quietly walked through the Museum’s thoughtful exhibits. Sadly, I discovered the same stories of betrayal repeated yet again, now documented in detail through the experiences of the Yakama.

But one story included in this long history of past injustices provided a small beam of hopeful light that eventually opened the way to a stronger and more equitable future for the Yakama Nation.

A Sacred Mountain Lost and Returned

In 1855, after years of armed hostilities between the Yakama and newly arrived white settlers, the US government presented a one-sided “treaty” to the Yakama, (accompanied by threats of violence) which forced them to cede more than 10 million acres of their traditional homelands. Even worse, the newly-drawn “official” government boundary map placed Mt. Adams completely outside the tribe’s already diminished territory.

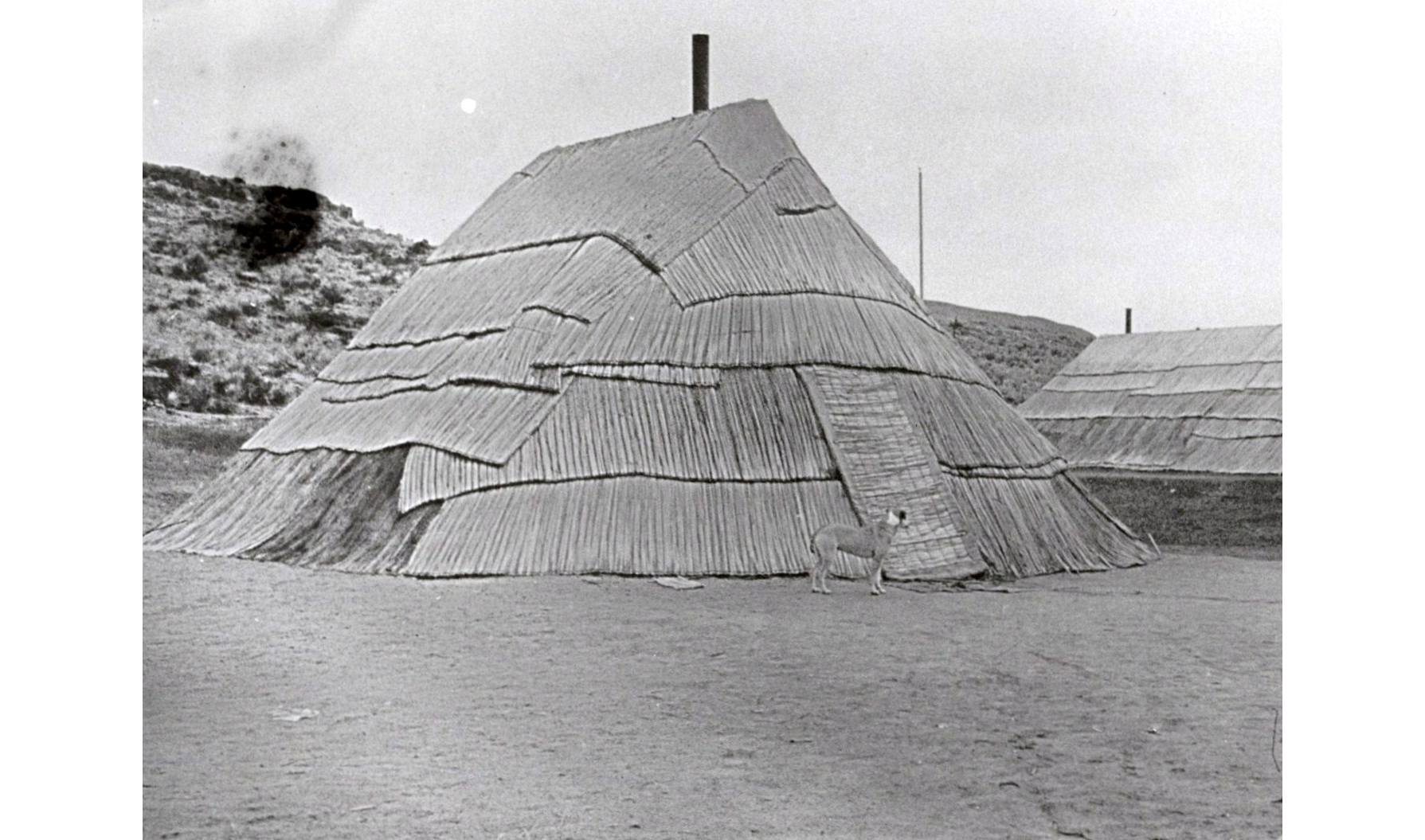

In the Yakama language, Mt. Adams is known as “Pahto,” a spiritual protector that the Yakama have revered for countless generations. During the summer months, tribal members traditionally gathered in the Klickitat meadows below the mountain’s foothills to pray, and to harvest medicinal roots and other foods for the winter.

Mother Nature is our Teacher.

We study her best when we are alone with her.

— Exhibit quote from Yakama Museum

Unfortunately, the original treaty map of 1855 was lost for nearly 75 years after it was “misfiled” by a federal clerk, and the map’s whereabouts was not rediscovered until the 1930’s. But a subsequent legal review of the map proved that the lands below Pahto’s eastern slopes were clearly within the boundaries of the Yakama reservation.

During the time of the map’s disappearance, federal and state agents had allowed a steady stream of new white settlers to file homestead and mining claims inside Yakama territory, making tribal access to Pahto even more restricted and perilous.

Finally. the Yakama Nation had endured enough. With a long-term vision for justice clearly in their minds, Yakama leaders began a decades-long public relations campaign to forge powerful alliances with other Washington state native tribes, knowledgeable land-use lawyers, and a determined team of dedicated lobbyists who collectively brought the Yakamas’ long-standing treaty grievances all the way to the White House.

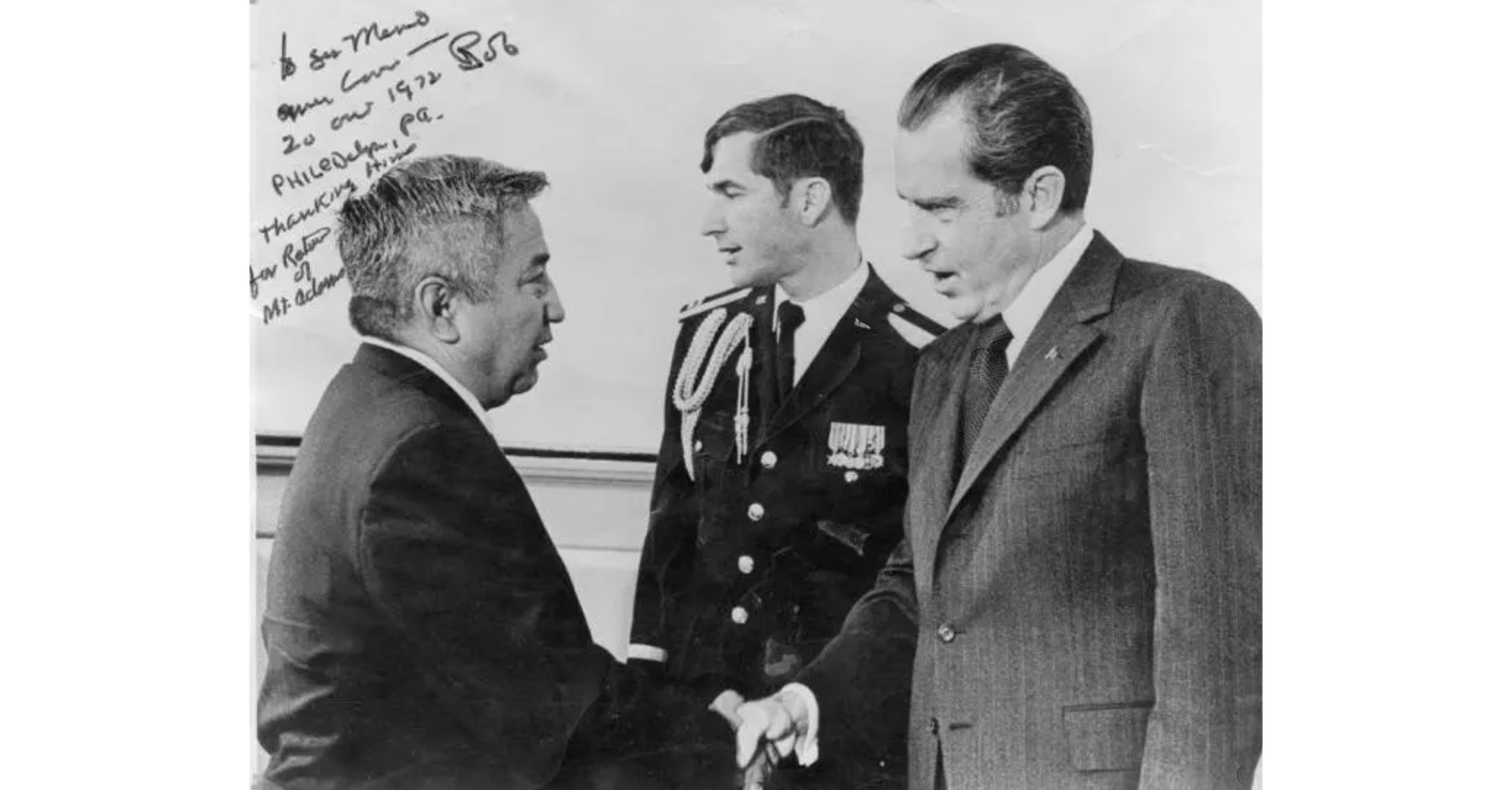

On May 20, 1972, after carefully reviewing evidence of the broken 1855 treaty and meeting in person with Robert Jim, a respected Yakama leader and experienced tribal negotiator, President Richard M. Nixon signed an executive order that returned thousands of acres of bitterly contested lands (including Pahto) to the 14 Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. This historic and long-overdue correction of a past treaty insult took 117 years to complete, but in the end the Yakama regained their stolen land —and their ongoing access to Pahto as well.

“The U.S. government lost the treaty map in its own files and by the time it was found, actions had been taken which had mistakenly displaced the Indians from this land.”

— President Richard M. Nixon, May 20, 1972

Afterword

Despite the celebrated 1972 return of previous territorial losses, Yakama land-use struggles have reappeared again in a new era. As of August 2025, the Yakama Nation is continuing to legally challenge several new energy development proposals (generated by non-native companies) that would further infringe on and desecrate what remains of several culturally and spiritually significant sites on Yakama territory.

Unfortunately, the many troubling stories of mistreatment and violation I describe above are still alive today for the Yakama and other tribes as well. But I am hoping that justice will eventually prevail.

My Homage to the Yakama Museum

I am indebted to Yakama Museum manager Heather Hull for providing me with information that clarified specific practices and customs that are important in Yakama cultural life. I am also deeply grateful to photo archivist Liz Wahsise for helping me obtain permission to feature several archival photographs from the Museum’s collections in this post to help visually illuminate the context of Wahpeniat’s story.

May the combined assistance and generosity I received from the Yakama Museum help bring Wahpeniat’s story to life.

Wahpeniat’s Story

My interview with Wahpeniat begins with a recitation of her name and a few common greetings spoken in her native Yakama language, and continues with specific remembrances of experiences and influences that have shaped her values and artistic work since childhood. Although her native name is Wahpeniat, she is also known as “Bessie.”

[This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.]

Sandra

You already told me that you received your Yakama name through a special ceremony when you were 12 years old. When you were named, was it from an ancestor, or was it somehow associated with basket making itself?

Wahpeniat

It wasn’t predetermined that I would be a weaver. My auntie, Sandra Speedis Wyman, is our historian on my mom's side of the family, so we go through her when we’re picking names so she knows what names are available. But I think when I was named it came from my father’s side of the family. I don’t know who the woman was that carried the name before me, but people were happy for me, and not all names that are received have a meaning.

Sandra

You got a lucky one, I think.

Wahpeniat

Yeah, we learned later in time that my name means, “One who makes good baskets.”

Sandra

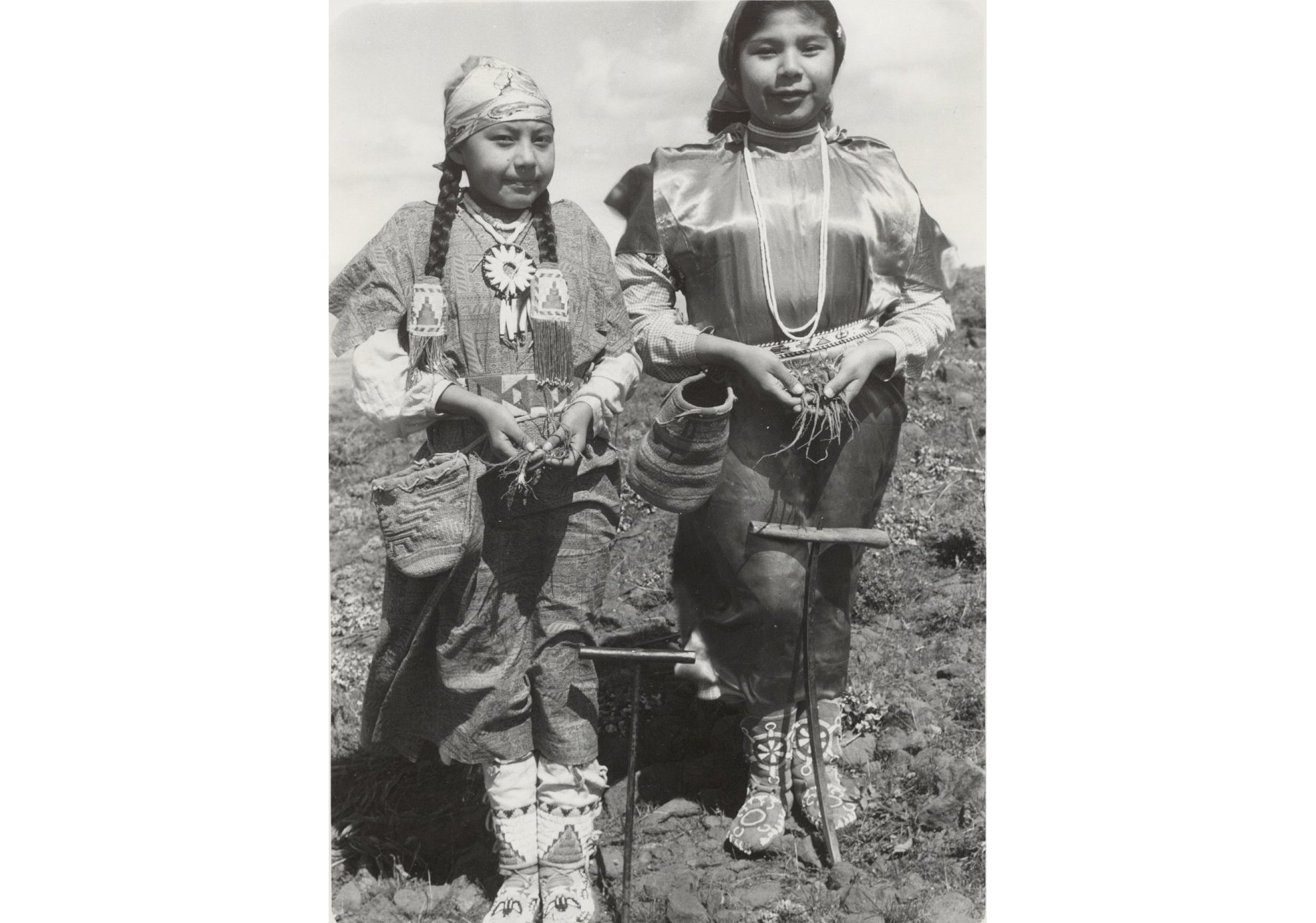

Amazing. That was meant to be. How did you begin learning the art of basket making, and what are your earliest memories of your root and berry gathering trips with your relatives?

Wahpeniat

When I was a young girl, my parents instilled in us a lot of our traditions and the things that we do seasonally. So we used to go pick cherries and apples in the fields, and then we'd also go dig roots.

Mom would show us how to identify the plants so we knew what we were digging, and we'd work together as a family.

Wahpeniat

I don’t recall a lot of memories of my childhood for some reason, but when I was about 12, the time I got my Indian name, my mom and her best friend who lived next door had a 4-H group, and we were called the Gliding Eagles. They would teach us different things, and weaving was one of them.

Vivian Harrison—she's one of our master weavers for the Yakama Nation—was invited in, and I remember sitting with her, learning how to make a wa’paas. And I still have that one, it's not too tall, pretty small.

Sandra

Are those the baskets that you take out to the fields where the roots are growing?

Wahpeniat

Yeah, that particular size though is too small for root digging and is used for decoration, but the larger ones I make are for wearing and gathering. And it seems like, with my parents, it was important that we learn how to take care of the foods, our traditional foods.

Sandra

That’s a great gift for you.

Wahpeniat

My mom also teaches preserving foods, canning fruits and vegetables. We did that in the 4-H group, and my mom is also well-known for her sewing of traditional garments.

About my dad: I went to a camp and I learned how to make a cedar bark basket that I brought home. My dad was so excited. He wanted me to share with him the process I learned. And then he started to make them. I had a little 12-inch one I made at camp, and then he was making these really huge ones and those are used for gathering huckleberries. When he passed away, a lot of those were gifted at his funeral, and people were happy to receive them because he had made them himself.

Sandra

Oh, that’s an even more powerful special gift.

Wahpeniat

I think the cedar bark baskets were the only ones I ever made with natural materials. I've always been taught with contemporary materials, like the craft cord that I use now and the yarn that you could buy at Walmart or any craft place. So I never really transitioned [from using natural materials]. A lot of people ask me what are the natural materials. I never really incorporated those, although I did take a class where I made a flat basket with hemp twine and yarn, and then I incorporated corn husk. It was just a little bit, like an inch of corn husk that I wove into it as part of that class. But I'd like to do more with corn husk.

In 2016, I took a free class to learn more about making wa’paas. I had moved back home and was living with my mom because I had rented my home, and I told her, “Let’s take this class!” She knew how to weave, but had just forgotten because she hadn’t done it in so long. So we took that three-part class, and you know how on social media you show off what you're doing. I’m like, “Look what I made.” And everyone said, “Cool! Oh, teach me, I want to learn.”

And this is part of my story: I share what I’m teaching.

Sandra

Well, we want to hear it.

Wahpeniat

[At first I’d say,] “Chaw tun Sapsakwatla.” “No, I’m not a teacher.” But I kept on making the wa’paas baskets because I did not want to forget how to start and finish them. So I kept making them. Then I’d show off on Facebook, “Oh, look at what I made.” It was in February, 2016, that I took that wa’paas class. By May, people were still asking, “Teach me, show me, I want to learn.”

Since I was taught that when people ask me and if I know how to do something, I should share my knowledge. And so finally, after many months, I said, “Okay, meet me here at the Longhouse,” and nobody showed up. And I said, “Meet me here.” We went to the community center and one person showed up, and I told my mom, “You know, I’m tired of driving and sitting and waiting for people who say they want to learn, I’m just gonna have it at my house, so that way I’ll just be home if nobody shows up.”

I put my physical address out on social media, and invited people: “Let’s do a potluck and let’s make wa’paas.”

That’s how the name of my classes came to be. That was May 2016 and around 37 people showed up. I didn’t have enough chairs and spots to sit for everybody. It was crazy.

And it was interesting, because there was people who came who already knew how to weave. “Oh, you don’t have to teach me, Bessie. I just heard you’re having a potluck and I wanna be around people.” And it reminded me of the quilting bees…

Sandra

Right, I remember my grandmother doing that.

Wahpeniat

…like in the past, when people shared sewing sessions or knitting skills. Anyway, everyone told me, “Can we do this again?” and “Can we come back next week?” So people were coming to my house once a week.

Sandra

That’s even more convenient. I mean, it saved you tons of time and energy.

Wahpeniat

So it started in my home. And then after a while, I start looking for places, and tribal programs let me use their conference rooms. Heritage University let me use a room. And so I was able to get around to different communities and not have people in my home. ’Cause sometimes there’d be a woman who would ask, “Can I stay longer? This is the only time I can work on my project.” Most people would leave by nine o’clock, but this woman would stay till midnight. I’d say, “Lock the door on the way out. I gotta go to bed.” It was nice not to have it at my home consistently.

Sandra

Yeah, that’s a big responsibility that you do not want. That used to happen to me when I taught, so I understand. “Now its time for you to go.”

Wahpeniat

Yeah, it was time!

Sandra

Okay, that’s really a fascinating story. I think you might’ve talked a little bit about that when we spoke together at the gallery, but this is more extensive and I love it. Thank you. Did you want to just briefly go over a couple of words about the baskets that you brought for this interview? Or is it just too cumbersome to drag them all out?

Wahpeniat

Yeah, it might be hard to explain them.

A lot of times when I’m weaving, it’s in my mind, and then it comes out of my hands. I can’t describe it. But there were designs I was doing where I thought, “These aren’t my designs. They’re just like coming from somewhere.” And my mom would look at it, and she goes, “Oh, that's suatash, those are clouds. Oh, this is this, and that is that,” and so I knew it wasn’t me. It was something being shared with me.

Sandra

Transmitted through you, I think!

Wahpeniat

After my maternal grandmother passed away, I was trying to work on a pair of moccasins, and I was just frustrated, because I couldn’t comprehend how my mom was trying to explain the process over the phone. So I went to sweat and prayed about it, and then that night I heard, because my grandma’s hands showed me the steps in a dream and she told me, “This is what you’re trying to get to.” The next morning I got up, and I did what she showed me, and I finished those moccasins.

I’m not adept at a lot of our traditional arts, but weaving for me became pretty natural. The designs came. Jan Whitefoot, she’s a local artist in Harrah, she has the Whitefoot studio, this beautiful work, paintings and…she approached me shortly after I was starting to weave and teaching weaving, and she said, “It’s not fair Bessie,” and I said, “Oh, what’s not fair, Jan?” And she said, “I had to go to art school to learn how to combine colors, and you’re just throwing them together like nothing!”

Sandra

You have a gift.

Wahpeniat

What’s funny is my nephew, who’s 10 now—at that time I think he was about two—had come to visit me at my home, and I’d have my yarn supplies laying out, and we’d play. He was still learning to walk, but he would lay out yarn skeins, skeins of yarn on the couch before he left, and I’d go, “Oh, okay, so he wants me to weave with these colors.” Sometimes they were very bizarre colors, but I would make it work. So it was his influence, laying them out for me.

And then my mom one time challenged me: “I want you to make six baskets using only purple, pink, and white.” But they all had to have different designs. So those challenges that she gave me really helped me think outside the box. And then I had an order from an elder for baskets that she wanted to give to her six granddaughters, so my mom had me make those six baskets that worked perfect. I was able to sell them to that elder…and they were exactly what she wanted.

One of my favorite stories is when I was at Mary Hill State Park. We go down there sometimes for birthdays and have picnics and swimming and birthday cake. And I was looking at the hills. It was springtime and I was like, “Oh, it’s so gorgeous,” and it was purple and green and yellow. So I went home, and I got those colors, and I started trying to weave what I seen. And then I gifted that basket to my cousin Jeanette, and she held it up and she goes, “Oh this is beautiful Bessie, it reminds me of the wildflowers in the Columbia River Gorge.” And I said, “Yes! That’s exactly what it is.”

Sandra

You know, Wahpeniat, when I went to Portland with my husband, we drove through that whole area, and I was also so amazed at how gorgeous it was. Just so beautiful with the wildflowers out. So I understand exactly what you’re talking about.

Wahpeniat

And it wasn’t like I wove flowers on a hill. It was almost like an impression of those colors that I had in my mind, and I was so happy that Jeanette got to see them in my basket.

Sandra

Well I’m sure that other people also feel what you are trying to express, even though it may be an unfamiliar skill for them, but you have it naturally.

Wahpeniat

Yes, and when I teach classes, I do the basics, one color blue, one color red, and as you twine, it’ll make vertical stripes. Just the most basic, or if you do horizontal stripes, you do this many of one color, this many of another. But as soon as I teach someone how to weave, their next question is always “How do I make designs?” or “How do I make it bigger?” Those are the two top questions I get.

Sandra

Your students want to know how to make a design from what you have expressed to them. That’s one way to learn.

Wahpeniat

Yes, I noticed I often choose designs that my mom calls “suatashes.” It's basically a triangle, and when I combine it with a plus sign, it looks like sideways triangle. My niece, who is 20, calls this design the “play button” from when you do gaming, and it cracked me up when she said that it was her interpretation of my triangle design. We both laughed, because I really wasn’t thinking of a “play button.” I was thinking of those neon-colored flags on a stick that hang sideways!

Sandra

Younger people have their own vocabulary.

Wahpeniat

I also make designs that show women or men together so it looks like they are holding hands around the basket.

Sandra

Well, what a wonderful odyssey you have engaged in with your life. And it sounds like you’ve had a lot of mentoring, not only from people that you know, but from almost psychic influences that a lot of people don’t really pay much attention to. And I work that way, too: it is really important for me to remain open to that kind of communication. So I’m happy that you honor a gift that was offered to you and that you accepted it.

Wahpeniat

Next May, it'll be 10 years that I've been teaching, so I’ve been trying to think how I can acknowledge that.

Sandra

Well, I’m sure you will. I think that a lot of things are changing in this era, and more people are becoming more attuned to the type of invisible communication that guides you below the surface.

Wahpeniat

The art show I had at the Boxx Gallery was a surprise. When they asked me to participate, I said, “Oh sure, I can get some pieces together.” And I actually had a hope to do petroglyphs that are along the Columbia River Gorge. And I only made one, the condor, but the other ones were so complicated, I didn’t have enough time to complete it once I had the idea. But I was hoping that I’ll follow through and maybe work on those and have them available.

Larson Gallery was interested in having some of my work on display. I do have some in their gift shop and I also have some in the Boxx Gallery gift shop.

I had a request from a museum in Tacoma, but they were wanting cedar root baskets and I don't do those. I’ve never made one of those yet, but I’m always hoping to learn and grow. That's one of my things. I don't ever want to stop learning and growing in this weaving. I don’t want to be stagnant. I want to always be open to new ideas and thoughts. I went to a basket weaving retreat, where I worked with cedar, and I realized how poor of a student I am, because my head was on the table and I was whimpering, because I couldn't figure out the concept of…

Sandra

Working with cedar and not with the yarn. Is that what you're saying?

Wahpeniat

Cedar and twine, instead of yarn.

Sandra

Yeah, that’s a little more challenging.

Wahpeniat

They were really big on willow baskets, which I’ve never made before but to me it felt like it would be too hard, like you have to have a lot of muscle strength, and I don’t. And it was interesting to me how few people knew my style of weaving, and they wanted me to come back as a presenter, as a teacher, but I was so busy last fall I wasn’t able to do the paperwork to be considered as a teacher, and I couldn't afford to attend. I got a scholarship last year, so I was able to afford it, but this year when I wanted to take my niece, and I was looking at it like, “Okay we’re not going. Not this year.”

Sandra

Yeah. Well, maybe next year.

Wahpeniat

Yeah. My niece is 20 and and she and I work together. I’ve been teaching her how to weave. I've been teaching her how to teach weaving, how to prepare the kits. And so she’s basically an apprentice, and we’re applying for an apprenticeship program where we’ll actually get money for the work we’re doing.

Sandra

You know, there are also some grants available through the state of Washington and through Artist Trust that you would probably qualify for. I’m going to give you some information about that, because living here in Central Washington, the grant makers actively want to support people in outlying areas, not just those who live in urban areas. I’ll get some information for you. You need to go forward. It’s time.

Wahpeniat

Yeah, I’ve been working on Central Washington University, the Pacific Northwest University, and Heritage University, school districts, and sometimes that only goes so far, and then I’m stagnant. I don’t have work, I don’t have contracts. So, sometimes that is hard financially.

Sandra

Of course I understand. I don't think I’ve ever made much money from my own art, except when I did illustration work, which is much more commercial. But my real work is just what it is. And I have to do it.

Wahpeniat

Yeah, and I know I’m not the only weaver. There’s many weavers out there that sell their work and share their work. And some of them I’ve taught, and some are my relatives. And, you know, I just respect everybody.

One time, this man was thanking me for helping him with traditional medicine ’cause he was really sick. So I went out to his home, and I showed him how to brew this tea, and how to put this together for this symptom. So in gratitude, he gave me three wa’paas, and I kind of laughed. I’m like, “Oh, so you’re gonna give a weaver some wa’paas?” He’s like, “Oh, is that bad?” I said, “No, it’s just, I'm amused. It’s okay, thank you.”

And when I turned them over, and I looked at the bottom, and I looked on the inside, and I looked at the designs of those three wa’paas, I knew who made them. I asked, “Did so-and-so make this one?” And he said, “Yeah!” And he was amused. And the second one I asked, “Did so-and-so make this one?” “Yeah, that’s just crazy.” And for the third one I said, “I think so-and-so made this one.”

Sandra

You recognized all the makers.

Wahpeniat

And he knew, he was like, “Wow, you are a weaver. Yeah, exactly. Those are exactly who I bought them from.” So, that’s pretty cool.

Sandra

That’s more than cool. It’s meant to be. It’s really special. You’ve been exposed to a lot of people ’ve helped you and encouraged you. And of course, s your job then to use that knowledge for your own work…to share with the world.

Wahpeniat

Right.

Sandra

You’re a world citizen.

Wahpeniat

Yeah, it’s hard when people are stingy. I wasn’t selling at first, because my goal was to make sure all my family members had a pretty wa’paas. “How come we don’t have a pretty wa’paas?” ”Well, you have to make them.” So, I started making them, and that was my focus, gifting wa’paas that were pretty to my family. And people kept asking, “Well, can I buy one? How much?” And so I start asking other weavers, “How much do you sell this size for?” And people were resistant, and they didn’t want to help me. So, I was surprised at that reaction, and I just kind of try to figure it out on my own.

Sandra

Were they jealous of you, do you think, or insecure?

Wahpeniat

Sometimes I think that plays a part. Like people get in a niche for something and this is their area. Maybe you’re stepping on their toes. But being someone who teaches classes, I get a lot of referrals. So I know there are people that support me out there. And so I just try to just keep moving. I don’t focus and worry about people who don’t want to share with me. I’ll just keep moving.

Sandra

Keep moving on. Yeah, that's the best way. You can’t change people.

Wahpeniat

Yeah, I don’t want to be pouty and worrying about things. Life’s too short for me to sit and worry about what other people think.

Sandra

Good for you. Now, you’ve mentioned the word “wa’paas.” Does that mean “basket,” or is it a special kind of basket?

Wahpeniat

Vivian Harrison told me that “wa’paas” is defined as any utilitarian bag.

Sandra

Okay, and how is that spelled?

Wahpeniat

It is spelled “wa’paas”, but some spell it wa’pus, because there are 14 different dialects within the Yakama Nation language group.

Sandra

Wow, I had no idea about that number of dialects.

Wahpeniat

I don’t know how many of those dialects are still alive. Many of our languages were dying out, But there’s been a big resurgence of effort to keep it alive, to have people keep speaking.

Sandra

That’s so important.

Wahpeniat

Yeah, ’cause even for me, the Yakama vocabulary I have is very basic compared to my late father, Tuss Tuss Johnny Bell Jr. He spoke fluently, and he was part of the Rock Creek Band, and had conversations with people. He would sit in our home, in the living room or out in the yard, and they would speak totally in our language, But we were never taught it, because of that boarding school history.

Sandra

Oh, yes! I have done a lot of research about this subject.

Wahpeniat

And so they didn’t want us to be punished for speaking our language.

Sandra

I understand completely.

Wahpeniat

People missed my dad when he passed away. And my mom is Wycush, Lucinda, Columbus, Topoc and Bill. My mom doesn’t speak it as much, but she can understand. And myself, I tried to learn when I was younger, and I took classes, but I haven’t kept it up. It’s hard to balance. I’m weaving, I’m teaching weaving, I’m sewing.

Sandra

Yeah, it’s a lot.

Wahpeniat

I’m involved in this dance group where I’m one of the mentors. I drum and sing, and I mentor the girls, and we teach them social dances. And I’m on the powwow committee for Yakama Nation Treaty Days. And so a lot of these things keep me busy, along with every weekend, usually I have my nephew, and we travel to powwows. You can only put your energy and time into so many things.

But I'm always hoping to learn and grow. That’s one of my things. I don't ever want to stop learning and growing in this weaving.

Braiding Sweetgrass — In this luminous and wise book, botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer (Potawatomi Nation) makes a lyrical and convincing case for reimagining our relationship to nature as mutually beneficial. Taking the reader from her classroom to her lab to her (enviably abundant) garden to a rainforest in Oregon, Kimmerer demonstrates time and again how working with the land, as opposed to shaping it to one’s purpose, is a method rooted in Indigenous tradition and borne out by science. Brimming with knowledge and a deep love for the natural world, Braiding Sweetgrass is a hopeful guide to a better future for all life on our planet and an absolute joy to read.

Member discussion