A Contemplation of Water

Streams are children of the ocean,

always following their elders.

Streams, the determined children,

Traveling on forever.

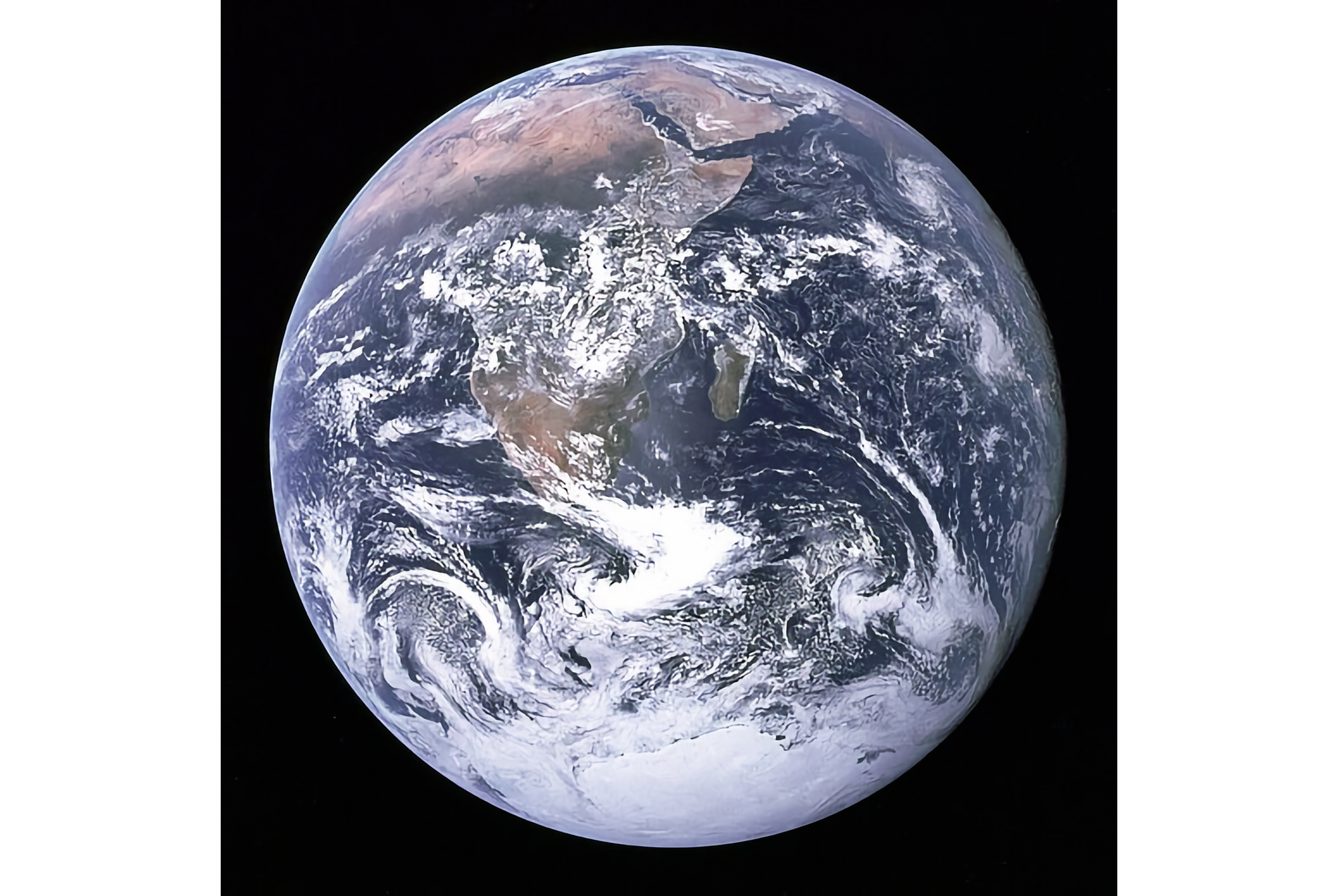

Our Only Home

The photo above, which first appeared in an earlier Art Nun Journal “postcard” titled, “Earth from Space”, shows Planet Earth, our only home, as a delicate, blue and white, pearl-like sphere, infused and enveloped with endless forms of moving water—streams, rivers, lakes, oceans, and water vapor—that combine to cover 71 percent of its surface.

In whatever form it takes, water is always on its way somewhere on its endless journey, as it attempts to form an organic whole by joining what is divided and uniting it through its great or small circulatory systems. This interconnected, planetary whole also includes microscopic life and the plants and animals that make up specific ecosystems.

In many ancient civilizations, water itself was once revered as a divinity—the great life-giver that ensured plenty for all communities. But with the advancement of the Industrial Age around the turn of the 20th century, water gradually lost its previous association with spiritual principles and began to be viewed through the lens of pure utility only: as a convenient means of commercial transport or as a profitable source of energy when once-thriving river systems were completely blocked by dams for quick financial gain.

In these past and less holistically aware times, the drying out of wetlands for development, the deforestation of river valleys, and the artificial straightening of mighty waterways through canalization at first appeared to be advantageous. But when life-giving underground aquifers began to dry up, salmon and other marine resources started to diminish or disappear, and the creatures (including humans) that depended on rivers and oceans to sustain their own food sources began to suffer, it became increasingly obvious that humanity had lost touch with the invisible vital coherence that exists within the earth’s natural and healthy regulatory systems.

Decades ago in Germany’s Rhine river watershed, environmental studies revealed that the natural forward course of water is a rhythmical, back and forth meandering. But more detailed follow-up investigations showed that even when a river is artificially confined by straightened side embankments of concrete, it will still try, with all the remaining strength it has, to recreate its customary rhythmical flow, now made even more powerful by its walled imprisonment. Not even the strongest of barriers can hold out indefinitely against the “will” of the water, and whenever an opportunity exists, these artificial confinements will eventually be eroded into oblivion.

The real-life trilogy of stories I include in this post, and the photos and artwork that accompany them, further illuminate some of the challenges and triumphs associated with the Earth’s threatened water resources worldwide.

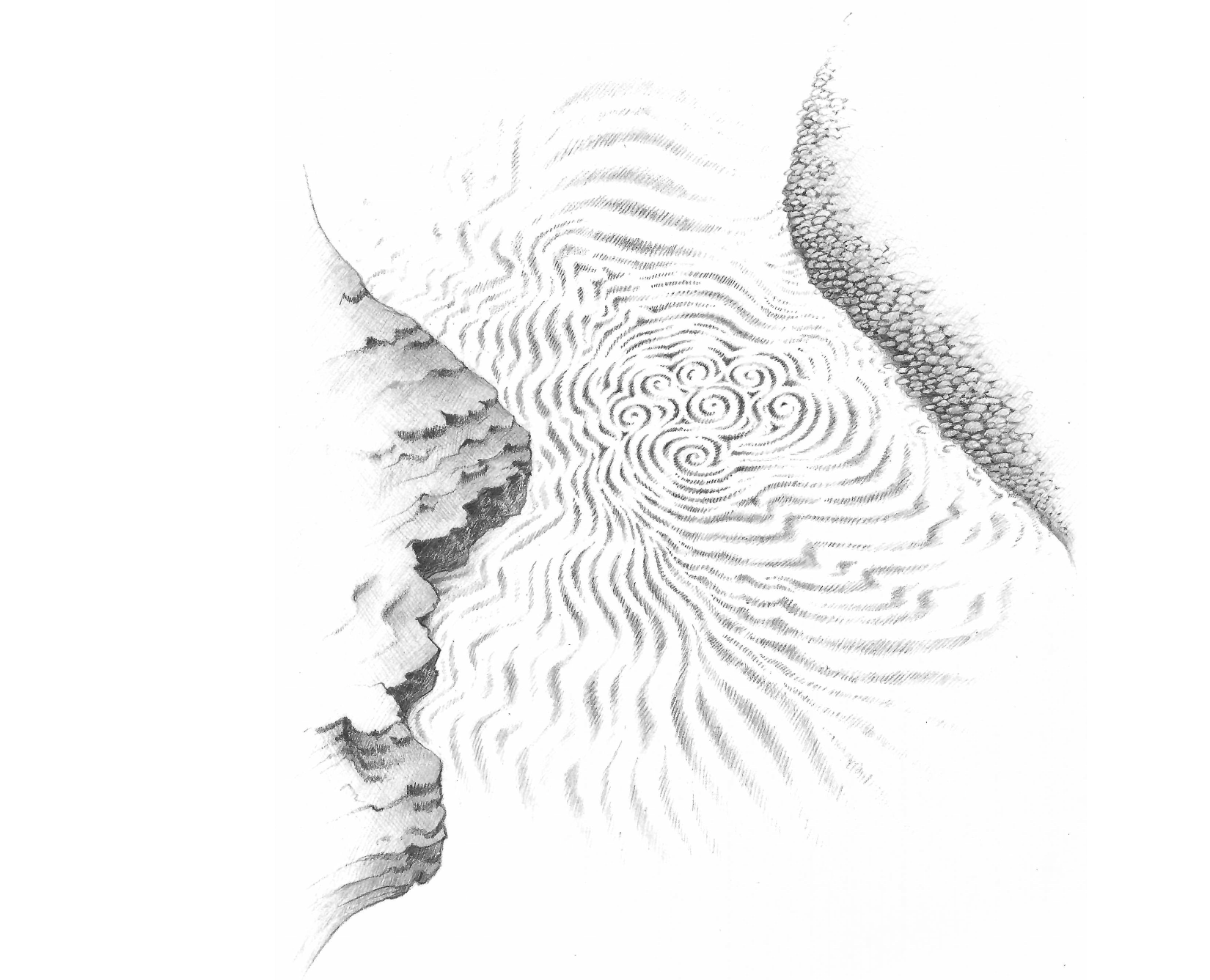

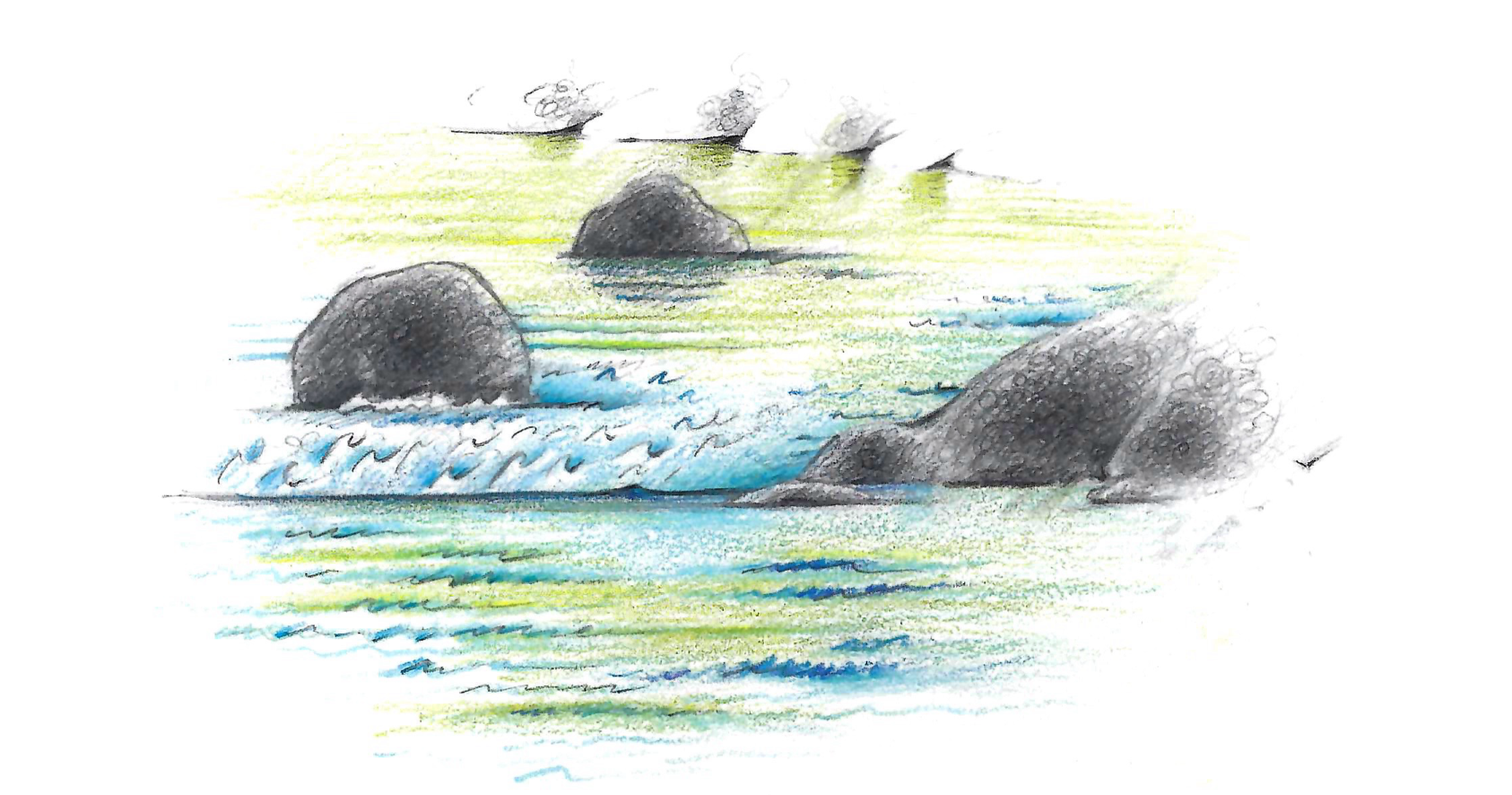

From top to bottom: Beautiful Cowiche Creek near Tieton, in Central Washington (Sandra Dean); Glacier Park Water Vortex, by Sandra Dean; Black Rocks in Breitenbush River, by Sandra Dean, 2005

A Promise Fulfilled at Last

For more than 160 years, the indigenous Polynesian people of New Zealand, the Maori, have been fighting to receive government protection for the Whanganui River, which flows 180 miles to the Tasman sea, through a rugged, lush, and forested high mountain landscape.

The Whanganui (Maori) tribes have nurtured a deep connection with this waterway for at least 880 years—more than 700 years before the first European settlers arrived. The river provided Maori communities with the physical sustenance—fish, game, shelter, and fresh water—that they needed to survive. But the Maori also revered the river itself as a source of spiritual inspiration and strength that is not separate from their own identities. The saying below sums up the traditional Maori view of their relationship to their beloved river and the Earth itself:

I am the river. The river is me.

In 2017, after years of contentious debate and legal investigation between the Maori and the federal government, New Zealand’s Whanganui river became the first river in the world to be recognized as a legally recognized “person”— bringing closure to one of New Zealand’s longest-running court cases. With this newly-enacted recognition of the river as as a legal entity, harming it is now seen as the same as harming the tribe. If there is any kind of abuse or threat to its waters, such as unchecked pollution or unauthorized activities, the river can sue. It also means it can own property, enter contracts and be sued itself.

The short film that follows takes you behind-the-scenes to meet spokespeople for the Maori world view, to learn more about how and why the government’s landmark decision finally became part of New Zealand’s body of law:

A Peruvian Environmental Heroine

The Goldman Environmental Prize was created in 1989 by San Francisco philanthropists Richard and Rhoda Goldman to honor ordinary people worldwide who take extraordinary actions to protect not only their local communities, but also the Earth itself. Over many years, Mari Luz Canaquiri Murayari has repeatedly risked her own safety to speak out against policies that cause environmental and social harm.

We do this not only for us, but for all of humanity and all beings.

— Mari Luz Canaquiri Murayari, a voice for the Earth.

Canaquiri Murayari, 56, an Indigenous Kukama leader from the Peruvian Amazon, has been fighting for decades to protect the Marañón River. The river is home to her peoples’ ancestors and is an abundant life-source for the larger rainforest ecosystems around her that keep the world livable.

Murayari grew up in the village of Shapajilla, along the banks of the Marañón river, a biodiverse area that is home to pink dolphins, giant river otters, jaguars, manatees and more than 150 species of fish.

The Kukama and other Indigenous peoples’ territories line the Marañón River basin, where they have lived interdependently with the waterway and its surrounding rainforest for countless generations. The Kukama are known for the rich ecological knowledge of their homeland and the healing abilities of the plants that thrive there.

But for decades, a powerful alliance of international and Peruvian oil extraction interests has desecrated the land, air and water in the Marañón region with toxic drilling waste and other pollution. For the most part, the oil companies have avoided prosecution by leveraging their government representatives to routinely ignore common sense regulations in favor of unchecked economic growth at any environmental cost. These shortsighted policies also view the Marañón’s existing ecosystems as useless, lifeless property—like an old car or a toaster.

In 2000, when a disastrous oil spill took place on the Marañón, Canaquiri Murayari and other Kukama women gathered together to question how oil extraction projects could be imposed on them without their consent. They founded the Huaynakana Kamatahuara Kana, or “Working Women” federation, which focused on protecting the health of their land, their ways of life, and the life of the planet as a living, interconnected whole. While speaking with lawyers at Peru’s Institute of Legal Defense a short time later, Canaquiri Murayari asked a simple question:

Why doesn't the Marañón river have the same legal rights that people or corporations receive?

In 2021, the Huaynakana Kamatahuara Kana federation filed a lawsuit to make that happen. The case, against various Peruvian government ministries, sought recognition for the Marañón River to exist, flow, and be free from pollution, among other protections. Canaquiri Murayari became the voice of that effort and continued to persevere in her public commentary, even though she was ridiculed, threatened, and harassed not only by members of the conservative Peruvian elite, but by her own government as well.

New threats to the Peruvian environment are already being planned for the future, which include a multimillion-dollar government dredging project that would turn the Marañón river into a shipping superhighway for oil and mineral extractions further upriver. Pollution has been taking place on the river for over 50 years, and has been compounded exponentially as nearby cities use the river as a collective dumping ground for untreated sewage or garbage. All of these examples are serious threats to the Marañón river and the indigenous people whose lives depend on its ongoing health.

In a 2025 interview with Canaquiri Murayari for Inside Climate News, the moderator asked Murayari why it was that indigenous women were most often on the front lines defending nature.

Canaquiri Murayari´s response was quick, to the point, and accurate:

It is because women are the most vulnerable and have been treated like objects before—without rights, disrespected, and dismissed. But now, we are empowering ourselves. We are taking action not just for ourselves, but for our children and future generations.

Fish With No Ladders

Long before the first white settlers began migrating to the north coast of Washington State to make land claims and search for jobs in the new, infant logging industry, some of the richest runs of salmon outside of Alaska crowded upstream to their ancestral spawning grounds in the headwaters of the wild Elwha River. At that time, the river ran freely through towering conifer forests that sheltered a diverse, living community of elk, black bears, cougars, eagles, and the homelands of the Lower Elwha Klallam tribe.

In the early 1900s, Canadian entrepreneur Thomas Aldwell saw the river as an economic opportunity for the future construction of two hydroelectric dams to be builit on the then free-flowing Elwha river. With financial backing from a group of wealthy Chicago investors, the Olympic Power Company was formed, and Aldwell began quietly buying up property after property that bordered the Elwha river so that construction of the dams could move forward unimpeded.

The construction of the Elwha Dam began in 1910 and was fully functional by 1913. The Elwha Dam initially supplied energy to a small pulp mill in Port Angeles, ultimately supporting the growing logging industry in the region. But as the economy grew, energy demands increased, and construction began on a second dam. By 1927, Glines Canyon Dam was built eight miles upstream of the Elwha Dam.

Though power generated by the dams helped to fuel the non-indigenous local economy in the first half of the 20th century, Aldwell failed to include fish ladders in the dams’ construction plans. This grave and obvious omission was never corrected, and returning sea-run fish were left with a mere five miles of accessible habitat from the mouth of the river. The dams also blocked large volumes of sediment behind their walls, whose weight contributed to the erosion of riverbanks, the deterioration of suitable spawning habitats downstream, and ongoing instability of the dams themselves.

Dam construction had additional negative consequences for the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe that historically lived along the river’s banks. Multiple areas of religious significance were flooded, and spiritually and economically valuable salmon populations were completely decimated.

Even though hydroelectric power lines were available to the more affluent white population living near Port Angeles when the dams were constructed, none were built on the Lower Klallam territory due to the tribes’ inability to pay for them. It was 56 years before an electric power line was finally extended in 1969 to serve the Lower Klallam tribe.

During the troubled and meager times that accompanied the Lower Elwha tribes’ existence after the turn of the 20th century, one of the young boys who grew up there remembered asking his elderly aunt why there were no power lines in his Lower Klallam community. According to the story that was passed down for generations, his aunt was silent for a few moments and finally replied:

We were poor, and everyone said that we were “just Indians.”

By the 1980s, salmon populations were threatened across the entire Pacific Northwest region. After years of political debate, Congress settled the issue in 1992 by passing the Elwha River Ecosystem and Fisheries Restoration Act, which authorized the Secretary of the Interior to acquire the two hydroelectric dam projects and begin full restoration of the Elwha River and its native fisheries. The Elwha Dam was removed in 2011, followed by the Glines Canyon Dam in 2014.

Though dam removal has been accomplished, the full restoration of the Elwha River ecosystem remains an ongoing process. The National Park Service hopes to continue its work with the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe and other partners to ensure that the Elwha River and its fish populations are once again vital and healthy.

My Art Nun Commitment

In the spring of 1996, I enrolled in an Environmental Science course at Seattle Central Community College, and in one of the first lessons, the instructor included historical film footage of 50-pound Pacific salmon desperately throwing themselves against the high timber barriers of the first Elwha dam as they tried unsuccessfully to reach their ancestral spawning grounds. I never forgot the pain I felt as I watched that archival film. I am certain that the powerful visual imprint it left in my mind influenced my world view many years later. Now, through the research, photos, artwork, and personal stories I include in my Art Nun Journal, and in this Contemplation of Water post specifically, I try to shift hostile environmental attitudes and actions towards a sense of greater awareness and reverence that is owed to the delicate, blue and white, pearl-like, water-covered sphere that is Our Only Home.

In this thought-provoking work, the laws apparent in the subtle patterns of water in movement are shown to be the same as those perceptible in the shaping of bones, muscles, and a myriad of other forms in nature. Fully illustrated, Sensitive Chaos reveals the unifying forces that underlie all living things.

Is a River Alive? is a joyous exploration of an ancient, urgent idea: that rivers are living beings who should be recognized as such in imagination and law. Robert Macfarlane takes readers on three unforgettable journeys filled with extraordinary people and places.

Return of the River tells the story of the largest dam removal in history, on Washington state's Elwha River. The film explores an extraordinary community effort to set the river free, and shows an unlikely victory for environmental justice. Told by an ensemble cast of characters, Return of the River offers hope amid grim environmental news, chronicling a dramatic success story that has drawn international attention to the Olympic Peninsula. This movie is available on Kanopy, a free streaming service offered by public libriaries. You can sign up with your library card information. It is currently (2025) available at the Seattle Public Library.

Member discussion